How short can a poem be, if it is to remain a poem? The Scottish poet and artist Ian Hamilton Finlay wrote a series of one-word poems (though the titles were often considerably longer). There are poems with no content, only titles, such as Don Paterson's 'On Going to Meet a Zen Master in the Kyushu Mountains and Not Finding Him', or James Wright's 'In Memory of the Horse David, Who Ate One of My Poems'.

I like those two, but often the 'litty' combination of brevity and levity falls far short of the mark set by the best comedians. Take Woody Allen's 'Eternal nothingness is fine if you happen to be dressed for it' or 'I am at two with nature'. Then there's Groucho Marx's delightfully surreal 'Outside of a dog a book is a man's best friend. Inside of a dog it's too dark to read.'

Essentially, very short poems are not that different from other kinds; they work (or fail to work) for much the same reasons longer poems do. So a short poem, like any other, isn't a poem when it is ONLY a set-up for a punch line, a sentimental platitude or a statement (political or otherwise) that would be better served in prose.

But what should one make of the following?

IMAGE

Old houses were scaffolding once

and workmen whistling.

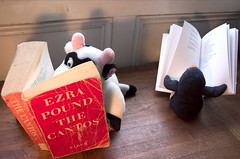

Some would dispute that T.E. Hulme's couplet is in fact a poem. I think it is (and so did Larkin apparently, who included it in his Oxford anthology). For me, the poem manages a kind of magic, a cinematic, reverse-time-lapse effect, running history backwards, undressing all those gaunt, respectable old houses we've seen and momentarily wondered about, leaving civilization without its facade, but with a cocky, human note, almost the air of a song. Hulme wrote little poetry (his Complete Poetical Works when it was published in The New Age in 1912 consisted of five poems); so it is remarkable that he is acknowledged as the founder of the Imagist Movement, which had such an important influence on Pound.

Many approximations of haiku, tanka, epigrams etc. have as much substance as soap bubbles, and none of the buoyancy. But when very short lyrics work they can trigger what Tobias Wolff might call 'synaptic lightning', allowing the reader to enter a space as startlingly expansive as the interior of Dr. Who's Tardis. Pound has some fine examples, such as his 'And the days are not full enough':

And the days are not full

enough

And the nights are not full

enough

And life slips by like a field

mouse

Not

shaking the grass

The kind of short poems that interest me are usually those with strikingly effective imagery, though there are exceptions, such as Oppen's 'There is the one word...'.

I've been reading Kuno Meyer's recently reissued 'Ancient Irish Poetry', which has a number of epigrams and short poems. Here's his translation of an anonymous poem from the 9th Century:

THE VIKING TERROR

Bitter is the wind tonight.

It tosses the ocean's white hair.

Tonight I fear not the fierce warriors of Norway

Coursing on the Irish Sea.

D.H. Lawrence wrote some memorable short lyrics. I took out my hefty Penguin edition of his Complete Poems, thinking I might discover many that were new to me (or that I had forgotten). I was a little disappointed to find only a few more short poems that held together for me, and to realise that many were rather dull. But I also came across some interesting things. The first paragraph of his introduction to his 1929 book, ‘Pansies’, is worth quoting:

“These poems are called ‘Pansies’ because they are rather ‘Pensées’ than anything else. Pascal or La Bruyère wrote their ‘Pensées’ in prose, but it has always seemed to me that a real thought, a single thought, not an argument, can only exist easily in verse, or in some poetic form. There is a didactic element about prose thoughts which makes them repellent, slightly bullying… We don’t want to be nagged at.”

Indeed; few people desire to be nagged at, or to read nagging poems. Lawrence wrote some remarkable poetry, especially about animals and plants. But he had very definite, often irritable and dogmatic, ideas about many things. Too often, the short poems are bursts of invective, flak from some war he seemed to be engaged in with certain kinds of English women and men; many amount to little more than framed Opinions. He acknowledges as much himself in the second paragraph:

“So I should wish these ‘Pansies’ to be taken as thoughts rather than anything else; casual thoughts that are true while they are true and irrelevant when the mood and circumstance changes. I should like them to be as fleeting as pansies, which wilt so soon, and are so fascinating with their varied faces.”

The weaker poems in ‘Pansies’ (and in Lawrence’s ‘Complete Poems’) are probably true enough to their time, though hardly less didactic or bullying than equivalent prose thoughts, and likely more pretentious. But the best of Lawrence’s short poems, just a couple of handfuls, are more than casual thoughts; these are perpetually fresh, classics of the genre.

So here is my nosegay:

THE WHITE HORSE

The youth walks up to the white horse, to put its halter on

and the horse looks at him in silence.

They are so silent, they are in another world.

THE RAINBOW

Even the rainbow has a body

made of the drizzling rain

and is an architecture of glistening atoms

built up, built up

yet you can't lay your hand on it,

nay, not even your mind.

SEA-WEED

Sea-weed sways and sways and swirls

as if swaying were its form of stillness;

and if it flushes against fierce rock

it slips over it as shadows do, without hurting itself.

NIGHT

Now that the night is here

A new thing comes to pass, eyes close

And the animals curl down on the dear earth, to sleep.

But the limbs of man long to fold and close upon the living body

of another human being

In shut-eyed touch.

NOTHING TO SAVE

There is nothing to save, now all is lost,

but a tiny core of stillness in the heart

like the eye of a violet.

LIZARD

A lizard ran out on a rock and looked up, listening

no doubt to the sounding of the spheres.

And what a dandy fellow! the right toss of a chin for you

and swirl of a tail!

If men were as much men as lizards are lizards

they’d be worth looking at.

NON-EXISTENCE

We don't exist unless we are deeply and sensually in touch

with that which can be touched but not known.

RELATIVITY

I like relativity and quantum theories

because I don't understand them

and they make me feel as if space shifted about like

a swan that can't settle,

refusing to sit still and be measured;

and as if the atom were an impulsive thing

always changing its mind.

LITTLE FISH

The tiny fish enjoy themselves

in the sea.

Quick little splinters of life,

their little lives are fun to them

in the sea.

Contemporary poets continue to be fascinated with making less more. Longley is obsessed with the short, imagistic lyric, and has written some memorable ones, Mahon too, and Heaney ('The dotted line my father's ashplant made...'). Muldoon's CRADEL SONG FOR ASHER is perhaps one of the greatest short lyrics of the century.

I've already written in an earlier blog about my recently deceased friend Anthony Glavin, who spent a couple of decades working on a long sequence of stunning 4-line poems, 'Living In Hiroshima'. If you're interested in seeing just how much it is possible to pack into such a small form, click on my entry for December 2006 and scroll down.

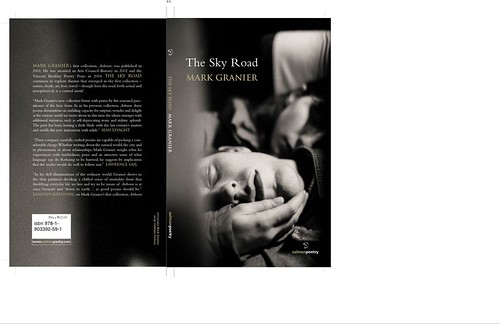

Here are four of my own shorter poems, the first two, DREAM ON and LIGHTBOX, are from my new collection, ‘The Sky Road’ (due from Salmon in April 2007). A 'lightbox' (from which I took the name of my blog), also called a roofbox, is the name given to the rectangular stone fanlight above the entrance to Megalithic passage tombs at Newgrange and elsewhere, angled to allow the rays of the sun to penetrate to the heart of the tomb.

The third poem, VANISHING POINT, is from my first book, 'Airborne':

DREAM ON

That little seal

of ownership, your fingerprint

on this mug of cold tea, after you're gone.

LIGHTBOX

(Newgrange)

Everyone should have one

dark hub for the dull day’s orbit:

stoneshouldered wings

where you bury the bones

of belief, and the redfaced sun,

to gain entrance, turns

a skeleton key.

VANISHING POINT

Simply staring

into the space ahead

is not enough; there is

the traffic of eyes to be met.

DARK MUTTER

Everything tends

to its own ends.

And my own haiku joke:

HAIKUISH

Haikush

Hash –

Ha

!

And finally, two from my recent collection,

'Fade Street', including my only one-line poem (or monostich):

NIGHT, WIND, DEAD LEAVES

rattle and hiss, the sound so high

it is almost a whistle,

their bodying sigh

the air of something more palpable

than passing by.

GHOST STORY

'Listen hard enough and you wake the dead.'