My aunt Nuala died on the morning of April the 9th, 2010. She was just a few weeks past her ninetieth birthday. Her children asked me to write something along the lines of a eulogy. My first thought was that I wouldn't know where to start, since Nuala has been so much a part of my life, particularly what are called the 'formative years'. But I soon realised where to begin, so things began to occur to me and the piece gradually took shape over the next couple of days. So this (with some editing) is what I read at the final stage of the funeral, the cremation in Mount Saint Jerome's:

Just a week before she passed away, Nuala left me a gift. Not directly, but in a talk with her son David. She told him that she remembered my original birthday. I never knew my father. But neither did I know, till last week, that Nuala was the only person present with my mother at the time of my birth, in the hospital at Islington. She remembered clearly seeing me lying on a towel, my first floor in this world. Nuala was my aunt, my friend and my second mother, and her children, my cousins Isobel, David and Susie, became, over the years, as close as siblings. I cannot remember how many years I spent with my second family in that amazing house in Avoca Terrace; I was in and out so often that it was more than a home from home; rather each of my homes was, to me, an extension of the other.

I was brought up by my mother and grandparents in a house called Rockville (perhaps because of the large rockery in the back garden). This house was on Stillorgan Grove, about half a mile from Avoca Terrace. If Rockville was not entirely dominated by my grandfather, his was certainly an important presiding spirit. The air was somewhat sober, an unspoken curfew was in place and late night chats in the kitchen were sternly discouraged (of course, not really that unusual in the 1970s). By contrast, Avoca Terrace really was a different planet, with a far lighter gravity. The largest, topmost apartment in a tall old Victorian terrace house, it was a place of landings, literally flighty, its huge, high rooms exfoliating off three steep staircases, the snaky-laddery stem of the building.

Nuala and her husband Desmond were both artists, and the evidence was everywhere: poetry books, books on music and art, a large heavy tome of Doré prints (with graphic illustrations for Dante’s Inferno), an old hard-backed copy of Ulysses that looked as if it had actually been read; on the walls oils, watercolours and reproductions of drawings by old masters, ceramics on the shelves and bookcases, little sculptures (such as the bronze Romulus and Remus on the mantelpiece that fascinated me as a child).

One room in particular, always known as ‘the orange room’ because of its old Tintawn carpet, was galleried with Desmond’s and Nuala’s marvelous landscapes, portraits and still lives. Its ancient, ceiling-high mirror enlarged the room even more. Portals were everywhere. The big window was full of trees and sky: all was light, buoyancy, space. Nuala and Desmond had met while students in the old NCA on Kildare Street. In the spirit of the times, Desmond courted Nuala, leaving a rose on her easel. However, somewhat contrary to the spirit of the times, both of these people were surprisingly modern; they were serious about their art, persevered with their studies and got their degrees. They were also adventurous, traveling separately throughout Europe for several years, before eventually marrying in Dublin and setting up home. And they were married for barely six years when Desmond died, tragically young in his 40s, shortly after the birth of their third child, so Nuala was left to the rearing of three young children.

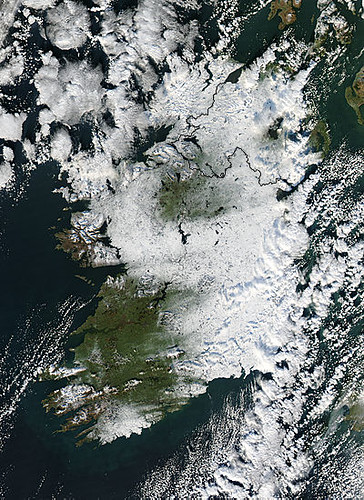

Nuala and my mother were close as it was, but Desmond’s death brought them closer still. We went on many holidays together, usually to the West of Ireland, Galway or Barley Cove in West Cork. Myself and Nuala’s children have vivid memories of one particular holiday when we shared a cottage (in or near Connemara I think). I had recently entered my frog and newt-hunting phase and there was a luxurious stretch of bogland behind the cottage: tall reeds, mossy grass, water. Time thickened; we spent whole days there, weeks, lifetimes, the hot sun on our backs, iridescent dragonflies stopping overhead, our hands steeped in the orangy water, looking for froglets, or the dark little flickery newts (with gorgeous Turneresque sunrises on their bellies) that we could never quite catch.

Another tradition was the shared Christmas dinners, and the big decision: whose house (or later whose flat) to hold them in? It was often Nuala’s, if only because they had the orange room with the enormous black-painted German walnut table. I have a whole box of photographs that charts our aging at that table, above the turkey-aftermath, the half-full bottles, shreds of wrapping paper in the background, red-eyed, flash-lit faces (the boys' becoming bearded, longer-haired then balding), fashion-paraded in differently bright-dark jumpers and blouses.

Perhaps I was too young myself (or too dreamy, as usual) but I have no recollection of witnessing the devastation that Desmond’s death must have caused. And though Nuala was a widow I would never have attached to her that rather grim title. Nuala’s perpetual youthfulness, her curiosity and delight in life, was intense and insatiable, and as teenagers this curiosity, coupled with her readiness to talk (almost any time of the day or night), was wonderfully liberating; a grown-up, from another generation, one that had experienced the upheaval of the second World War (or The Emergency), yet she might have been one of us.

But of course she wasn’t. She was a mother who, like any mother, fretted about her children. But she also bequeathed on them her adventurousness and eagerness to travel, her curiosity and love of conversation and the arts (not to mention a wealth of talent ); she gave each of her children what Patrick Kavanagh might have called ‘a flavour of personality’; they are each, distinctly, themselves, comfortable and at home in their own skins.

I should mention Nuala had a great sense of humour, sometimes girlish and giggling, and often far from politic; when out ‘with the girls’, Nuala or Sheila, one might find oneself attempting to make like a chameleon in the face of a high-pitched voice commenting, quite loudly, on someone nearby (in a café, bus or cinema): ‘Look at that man, isn’t he odd!’ or ‘Is that a boy or a girl?’ Nuala’s humour could also be sharp and sophisticated; she wasn’t above slagging you off. Like my mother, she had a great eye for colours, and would often tell me if my mine were mismatched. Her elegant daughters, like myself, were children of the 1980s, and Nuala could never quite appreciate their love of all things black. Not that many years ago, she confided in me (what was apparently a very old joke, though I hadn’t heard it before): ‘I call them the Little Sisters of The Avoca.’

So our universe was ruled by the female principle; ‘the mothers’ were a driving force. Both Nuala and my mother encouraged me to enter what was then Dún Laoghaire School of Art. They took seriously my attempts at writing, they nurtured. When my grandparents died I was living in Bray; my mother had Rockville to herself, so it was natural that she should wish to move out of that too-large-and-lonely house and settle in Avoca Terrace, in the hall flat, beside her sister. And when I came to live with and care for my mother a few years later, in a sense everything clicked into place. It was a kind of homecoming. It was my world, and it still is (and now it is also a home to my wife and our child, my mother’s grandson).

For this, and everything else, I give thanks to Nuala, whom I will miss.