In the top drawer, so different from

the

soft, neatly folded clothes: her necklaces ––

pearls

and beads, the pink coral

trickle

and click through my fingers –– feel

the

precise weight of the tangle

of

memory and dream.

*

Fatherless, my secret terror

is that some abrupt power may snatch her, freeze

my panicked ten-year-old stare through the windscreen

(for almost a whole half hour)

at the corner of the shopping centre where

she must reappear –– now! –– so my world can snap back.

*

Just once, at her dressing

table, pawed

by my anxiety (‘but are you really

my mother or, or…’)

she swings round a scary-alien-face: ‘Ha!’

*

Her

gentleness scales down the fear

of

girls –– women with all their marvelous difference

never

too strange or too far.

*

Yet sex is part of the great

unspoken, an ‘information’ booklet: blotchy

grey and white photos, the girl’s pubescent v

retouched to a modest blur ––

like her life-drawings, the shapes

worried and tentative, furred.

I will have to find that bare continuous line

for myself.

*

Her eye is for colours lifted

from

an Irish landscape –– mossy and warm ––

or

seascapes, like one she sketched

from

the deck of a boat towing

yellowy

moonlit waves, the African coast’s

mountains,

taller than Dublin’s

and

inset with pale cities: our day trip

from

Torremolinos to Tangiers

receding

as we watched, at home between continents.

*

Innocence,

yes, though neither naïve nor saintly ––

a

working part of her instinct: second eldest

in a

family of seven, calm

at

the eye of the tantrum: ‘Oh,

I was

always the peacemaker’.

*

The heavy-headed roses have grown

dishevelled,

swaying above her

as

she stoops with secateurs

among

straight, woody stems, extravagant thorns,

burying,

I once pompously wrote,

‘her

regret’ (At what? Not having lived

a

more ordered or wildly-lived life? Not being sure

of

herself or what she should do?).

More likely just pleasuring, becoming lost in

velvety

pinks, creams, carmines

curling

like old photographs

tattered

and edged here and there

with

tea-brown stains.

*

In a

narrow alcove above her bed, plyboard shelves

sag a

little, like hammocks, under the weight

of

her cluster of books: Linda Goodman’s Sun Signs,

Belloc,

Betjeman, A Child’s Garden of Verses,

Winnie The Pooh, The Larousse Encyclopaedia

of Greek Mythology, a Dream Dictionary (that warns

against

dreams about weddings: funerals

in

disguise), James’s Michener’s Iberia:

grown-up

black and white photographs

of

hot dust, sharp shadows, blood, sweat, age.

What

else? The Wind In The Willows, Leaves of Grass.

*

Searching her room for Photoplay or She ––

glossies that might (unlike the

monochrome Lady)

reveal a lucky breast, I lift

the mattress

and find a Cosmopolitan that unfolds

a naked, hairy Burt Reynolds (his

flashy grin

sporting a bent cigarillo) on

a bearskin,

one elbow propped on the

white-fanged muzzle,

a protective forearm lax

between his thighs.

A man, masculine and

vulnerable, absurd

as my own pink fantasies, the TV ad:

‘…and all

because the lady loves Milk Tray’ ––

her long-vanished

brand of cigarette, Kingsway

(a

white pack with a red ribbon and gold crown),

her

style –– the way she wore scarves, belts, slacks,

touches of

elegance, flourishes, grace-notes

on a graph of

yearning, how high and how far ––

thirty

years to celebrate, to love her

for making ‘a little something’

of her own desire.

*

There

was Pound’s Fascist rant:

‘Oh how hideous it is

To

see three generations of one house gathered together!

It is like an old tree with shoots

And

with some branches rotted and falling.’

Then

Raymond Carver’s (quieter, more honest) ‘Fear

of

having to live with my mother in her old age

and

mine’

and here we are, and the

greater fears

go

blundering past like gale-force

window-rattling

golems, far

too

overblown to get a foot in the door.

*

As the home-help women help

my mother out of her clothes

and, if she can make it,

onto the shower stool,

some stay silent, while others

sprinkle a few words, names

like Darling or Dear. I think

she prefers the names. I do.

They drive from M50 estates ––

Clonee, Tyrrelstown, Blanchardstown,

late of that dusty-green cloak

of a continent –– carrying

the business of the world

helping, into our home.

And their own names sound like endearments –

Ola, Ayesha and the one

who is coming on Wednesday: Purity.

*

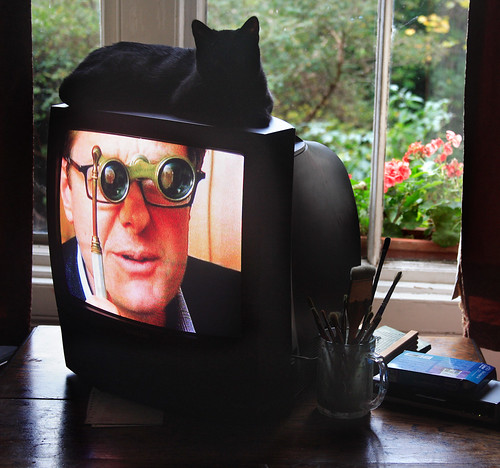

An afterlife: arthritic, room-bound

with

one of our cats, Claire, Hillary, Toby…

comfortably

draped on the TV’s

sleepy

cornet of Coronation Street

or The Antiques

Roadshow

while

a bright patch of winter sun dulls

the

orange coals: ‘Is it bad today?’

‘Ah yes,

singing

in my bones.’

*

But I remain wary of this

premature

mourning, however inevitable,

admiring

her doggedness, how on that slow train

boarded

at the end of the first World War,

her

‘proper’ age never arrived,

so,

at 93 (with her two sisters

nearest

in age gone like supporting walls),

she

confides as if for the first time:

‘It’s hard getting old.’

*

She’s

driving a little too fast, as if we didn’t have

this

whole day to tunnel through –

high-hedged

shuttle of fields, hills, sky

a

ladder of cloud-ribs, shadow-flits. She smiles

at

something I can’t guess and the road rises

and

plunges steep enough for a gulp

of

vertigo as the canopy unzips and I see

ahead,

slate-blue roughed with white, some cove

we

visited so long ago I remember

the

nested stones, cool sand. She turns to me

with

that smile and makes it mine.

The above is excerpted from a loose sequence I was working on when she died last February. It feels odd to post this, a bit transgressive, almost a violation. I remember Philippe Jaccottet's visceral disgust (expressed in a poem of his) at the very notion of a writer bringing specific biographical details concerning a loved one, or anyone close to him/her, into a poem. But then I also remember Patrick Kavanagh's lovely poem in memory of his mother:

'O you are not lying in the wet clay,

For it is a harvest evening now and we

Are piling up the ricks against the moonlight

And you smile up at us - eternally.'

For it is a harvest evening now and we

Are piling up the ricks against the moonlight

And you smile up at us - eternally.'

Or there is Heaney's poem from his (not at all loose) sequence of 'Clearances', about remembering peeling potatoes with his mother while he attended her death-bed:

'So while the parish priest at her bedside

Went hammer and tongs at the prayers for the dying

And some were responding and some crying

I remembered her head bent towards my head,

Her breath in mine, our fluent dipping knives–

Never closer the whole rest of our lives.'

And some were responding and some crying

I remembered her head bent towards my head,

Her breath in mine, our fluent dipping knives–

Never closer the whole rest of our lives.'

So there are certainly precedents, not that I can ever measure up to them.

In any case, Happy Mother's Day mum.