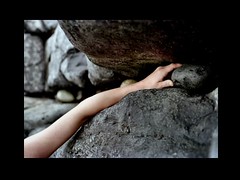

I remember someone (it may have been one of Don Paterson's aphorisms) comparing a good poem to a kind of secret door in a rock-face; once you found the way in you were presented with an unexpected vista, a whole, roomy landscape you hadn't expected. Then you left the poem, without quite remembering the way in or out. I think I remember Heany talking about something similar, which he might have referred to (riffing on Larkin) as the "poem with a hole in it"; the poem with a certain 'extraness' that resists easy elucidation: once you try to break it down into its constituent parts the door (or the hole) vanishes.

That's one way of putting it, perhaps to close to cod-mysticism for its own good. My point is that I prefer poems with some permeability, that allow for a little absorption. I don’t mind if I am slowed by some surprising linguistic texture, so long as I am able to reach in and explore around it; and so long as its shape seems pertinent to the rest. I can certainly enjoy a poem whose meaning eludes me or at least "resists my intelligence"; I don't think Bishop's At The Fishhouses is 'easy' (not to me anyway), but I trust where it takes me. Its sensuous but exacting imagery has what Reginald Shepherd might call "palpable texture." So does Komunyakaa's Facing It. So does 'The Waste Land'. So do short stretches of The Cantos.

Some poems are all but impermeable though; deliberately flat, fragmented, disassembled then bodged together again with parts conspicuously missing. You can solve such poems in the way you can a crossword puzzle, if you're good at cryptic clues and allusions. But it seems a thankless task to me (I'll admit I'm crap at crosswords).

Auden (who sang the praises of the permeable limestone landscape) called poetry "memorable speech." I think great, or even just good, poems should have at least an element of this; they should resonate in the way that a good song or piece of music does. If they manage that I will forgive them much, including a good deal of impermeability.

3 comments:

It's not a poem, but the sentence I consider a prime example of a "text with a hole in it" is the first sentence of "One Hundred Years of Solitude":

"Many years later as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice."

The word "ice" is the hole.

Dear Mark,

I quite liked this post, but I am writing to respond to your response to my most recent post on my own web log. I wrote this as a comment on that blog, but I wanted to make sure that you got it, and I could not find an email address for you.

First, thanks for your response. I did consider that perhaps I had overreacted to the use of the word "presumptuous," but it really got under my skin. Forgive me if I have misunderstood, but I read you as saying that aspiring to be a major poet was presumptuous.

I didn't intend to engage in any sort of personal attack, and certainly the thought that you would have tried to keep me from escaping poverty never entered my mind. I'm very sorry if my piece came across that way. I intended a more general statement about my response to the notions of propriety that I read into some of your comments.

The use of the word "presumptuous" with regard to ambition did and does strike me as having a strong element of enforcing a certain notion of propriety. Your first response referred not just to dividing other poets into major and minor as presumptuous. This is a fair enough charge, though I think that we all do that all the time, whether we admit it or not. We all decide that some poets are more important than others, although we may not articulate it in those terms. ("My favorite poets" is a version of this process. Who doesn't think that his or favorite poets are better than the poets he or she doesn't like?)

As I read it, your response also said that to want to be a major poet was presumptuous. To my eyes, your most recent response confirms that reading by saying that even if one nourishes ambitions to majority, one shouldn't speak of them, or at least that it's "pointless" to do so.

If I misrepresented you, I am very sorry. As I said, I responded very strongly to one portion of your comment and perhaps didn't take in the rest as fully as I should have. I apologize for that.

But I also think that we have a difference in viewpoint. It is clear to me that some poets are more important than others. The world is awash with poets who have no reason to be writing, who make no difference to the world of poetry. I'm not speaking of the outright bad poets, but of the sea of depressingly competent poets of no consequence, though sometimes of undeserved reputation.

Richard Strauss supposedly said "I may not be a first-rate composer, but I'm a first-rate second-rate composer." While I both admire his clear-eyed self-evaluation and recognize the boast within it, I am not so sanguine. I want to be a poet who matters and I want to read poets who matter, and I see no problem in being frank about that ambition. I also have no problem being frank about my judgments of other writers. I have faith in my own judgments, as you undoubtedly have faith in yours. I see no reason to pretend that I don't.

Thanks for reading and for your thoughtful and perceptive comments, and again, forgive me if I have misrepresented you.

all best,

Reginald

Dear Mark,

Again, I have posted this as a comment on my own blog, but wanted to make sure that you got it.

Thanks for another thoughtful response, and my apologies if I misunderstood you yet again. I took not seeing the point in something to thinking it pointless. Speaking of cultural baggage, that's what I would have meant by it. I shouldn't have put the word in quotes, though they weren't scare quotes; I honestly misremembered.

Speaking again of cultural (and personal) baggage, and speaking also completely frankly, for a number of reasons having to do with race, class, and my own personal history, to be called presumptuous makes me angry. If you'll pardon the pun, I find it presumptuous. That anger likely blinded me to the ways in which we were actually in agreement.

Though I take your point about pigeonholing poets and people, and obviously have argued against that on many occasions, I'm not sure that a word like "major" can be used without some implicit comparison to what's not major, whether one calls that "minor" or something else. The distinction, how it is to be made and what it means, is one that troubles me. I worry about making it, and I worry about not making it. By Eliot's criteria, almost every poet who ever wrote is a minor poet. (In my heart, of course, I wonder, "Would I be among them?" and fear the answer.) As Mae West reputedly said, goodness has nothing to do with it. Or at least, for Eliot poetic excellence is at most a necessary condition for poetic majority, but hardly a sufficient one. I wouldn't want to emulate such sweeping judgments as he makes in this matter. But still, the question troubles me, perhaps only due to my own personal ambitions as a poet (not the same as my poetic ambitions as a poet).

But I agree with you that enough is enough. I was quite argumentative in my youth, but now I find arguing with people, especially on the basis of misunderstanding, tiring and depressing. So my apologies once again.

I have rephrased the paragraph in "Daring to Disturb the Universe" so as, I hope, to remove the problem.

Take care, and as always, thanks for reading and commenting so thoughtfully.

yours,

Reginald

Post a Comment